Aperture is one of the three parts of exposure. It controls two things: the amount of light that reaches your camera’s sensor, and depth of field. Let’s get started!

What is Aperture?

Aperture refers to a hole inside a camera lens that opens and closes letting in more or less light. If you think about a lens like an eye, aperture is the iris (colored part of your eye surrounding the pupil). Tiny muscles in the iris control the size of your pupil. Aperture blades are like those muscles.

When it’s dark, your pupils grow to let in more light. When it’s bright, they shrink. Aperture works the same way. When it’s dark, you can open your aperture to let in more light. When it’s bright, you can close your aperture to prevent too much light from reaching your camera’s sensor.

Aperture as a Setting

The setting itself looks like this: F/1.4 (read “f-stop 1.4”)

“f 1.4” is the common way to say it. The number (1.4 in this case) is the only part that changes. Most lenses have an aperture range that falls between F/2.8 and F/22. There are specialized lenses called prime lenses that have wider apertures (apertures less than F/2.8), and some lenses have narrower apertures, especially lenses for cameras with larger sensors.FAQ1

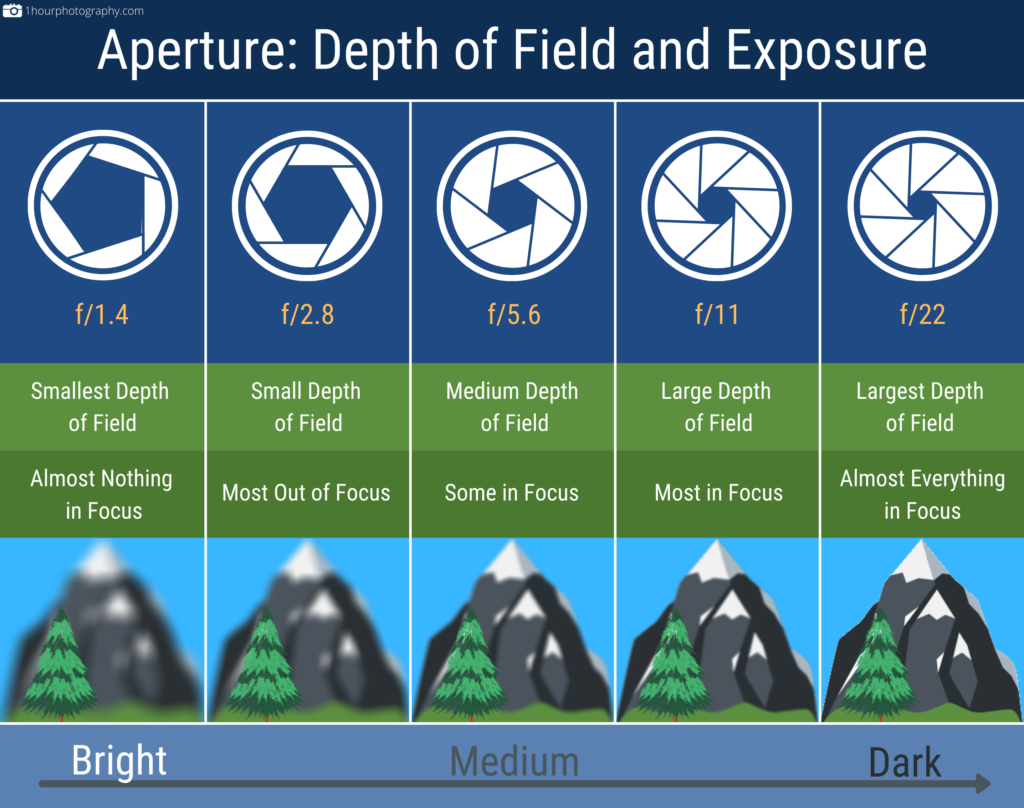

Aperture settings seem confusing until you know they’re fractions. Time to channel elementary school. 1/2 is bigger than 1/8. Simple. So, a lower number such as F/1.4 means the aperture is bigger (more open) and lots of light is let in. A higher number such as F/22 means the aperture is smaller (more closed) and less light reaches the sensor.

Aperture and Depth of Field

Aperture does not only affect brightness. It also affects depth of field (DOF). DOF refers to how much of the image is in focus. Closing the aperture (increasing the F number) increases depth of field. This means near and far objects will be in focus. Opening the aperture (decreasing the F number) decreases the depth of field and only puts one part of the image in focus.

The same aperture setting does not mean the same thing on cameras with different sensor sizes. Depth of field (DOF) is affected by the size of the sensor your camera has. Full frame sensors are the standard of the photography world and all the above settings are for full frame cameras. To convert aperture DOF to your camera, read my article on sensor sizes.

Aperture Stops

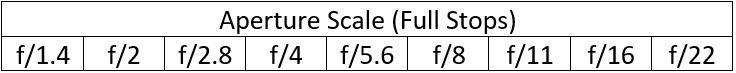

Aperture is sometimes talked about in “stops” of light. A stop of light is a unit of measurement, like an inch or a pound. Increasing the aperture number by one stop means cutting the amount of light that reaches the sensor in half (remember higher number = less light). Decreasing the aperture number by one stop means doubling the amount of light that hits your camera sensor (lower number = more light). The following table shows the change in F number necessary to a change one full stop of light.

By default, most cameras change aperture in 1/3 stop increments. This means, for example, that it would take 3 dial movements to move from f/5.6 to f/8 (1 full stop). People often talk about changing aperture settings in terms of “stopping” up or down. The meaning of this is simple.

Stopping up is opening the aperture by one full stop of light (Ex. Going from f/4 to f/2.8).

Stopping down is closing the aperture by one full stop of light (Ex. Going from f/4 to f/5.6).

Aperture and Low Light

Low light and nighttime photography require a lens with a wide aperture to gather as much light as possible. Your pupils dilate at night for the same reason. It helps you see. A wide aperture helps to reduce noise because the added light means ISO doesn’t need to be so high. Having a wide aperture also helps with camera shake. To be able to take handheld shots without getting blurry images, you need a high enough shutter speed. At night, there isn’t much light. Without a wide aperture letting in lots of light, shutter speed must be higher. The higher the shutter speed, the higher the camera blur.

Diffraction

This is one aspect of aperture that not many know about. Diffraction is the bending or spreading of light caused by running into an edge or passing through a narrow object. As you increase the f number, diffraction increases. This is why lenses lose sharpness at higher apertures. That bending of the light entering your camera causes interference and ultimately leads to softer, lower quality images.FAQ2

If you’re interested in learning more, check out this video.

Lens Corners and Aperture

You may have heard that lenses have an aperture “sweet spot” of image quality and sharpness.FAQ3 It’s true. We already know why higher f numbers can’t be the lenses sweet spot. Diffraction.

But why not lower apertures?

The corners of lenses cause image quality problems. Lens manufacturers can easily design the center of lenses to be sharp, but those corners are tricky. Lens corners are only a problem at wide apertures because the light from the corners only reaches your camera’s sensor at wide apertures. That’s right. Closing your aperture actually stops the light from parts of your lens glass from reaching the sensor.

The light that does enter the lens is still distributed to the entirety of the sensor. That’s why your images don’t have black, rounded corners at higher apertures.

You might be thinking, “I know I’ve seen crystal clear images that must have been taken at a wide aperture”. You’re probably right. It is possible to design and manufacture lens corners to provide sharpness even at extremely wide apertures, it’s just expensive. Lenses that can shoot sharp at wide apertures cost thousands of dollars.

Aperture Settings for Different Types of Photography

What aperture should you use for portraits, landscapes, wildlife, sports, and macro?

f/0.70 – f/2: Lenses with apertures in this range are hard to come by at the lower end and plentiful at the higher. These will be fixed focal length (prime) lenses. These apertures are fantastic for low light and nighttime photography, as well as portraits, wedding photography, and any photo where you want extreme bokeh (out of focus background).

f/2.8 – f/4: Lenses with apertures in this range are likely cheaper than the previous range and start to include variable focal length (zoom) lenses. These apertures are still great for weddings, portraits, and taking photos in mildly dark conditions. New areas these apertures are great for are sports, wildlife, and street photography.

f/5.6 – f/8: These apertures can be found on almost every lens and are where peak sharpness is often achieved. These apertures are great for almost any kind of photography. There is a nice balance between depth of field and amount of light. Context is present in most images taken in this range.

f/11 – f/16: Landscapes, real estate, architectural, and macrophotography. This aperture range keeps things sharp. The effects of diffraction begin to creep in.

f/22 and up: This range is rarely used and probably shouldn’t be unless you have a medium format camera. Otherwise, diffraction can be a real issue.

Note: The uses and types of photography listed are for full frame cameras. There is overlap with other sensor sizes. For the types of photography that are depth of field dependent, convert to the full frame equivalent setting. To see how to do this, read my article on sensor sizes.

Flash and Aperture

If you use on-camera flash, a speedlight, or a strobe, you need to know how aperture affects them. Shutter speed is usually in the exposure equation, but not when using flash. When using flash, shutter speed is only affected by the ambient light. This is because flashes happen so quickly. Shutter speed will be longer than the flash, so changing it to be longer won’t affect flash exposure.

Aperture on the other hand, is just an opening. If that opening is bigger, more of the light from the flash reaches the camera sensor. If it is more closed, less light reaches the sensor. Be mindful of your aperture setting when using flash.

FAQ

1. Why can cameras with larger sensors use narrower apertures?

Aperture is not a specific sized opening. It is a fraction based on the size of the sensor. On a full frame sensor, the setting f/22 results in a wider opening than f/22 on an APS-C sensor. This is why depth of field is different at the same settings on cameras with different sensor sizes. It’s also why the negative effects of diffraction are worse on cameras with smaller sensors. Apertures above f/22 only start to make sense for full frame cameras and are only widely used on cameras with medium format sensors.

2. At what aperture is diffraction too bad to use?

This question does not have a simple answer. It depends on the size of your sensor, because diffraction is worse at smaller openings, and the same aperture settings on cameras with different sensor sizes do not result in the same size opening. It also depends on the lens and camera you have. The affects of diffraction may appear worse on some lenses than others. Unfortunately, you need to check for yourself.

3. Where is the sweet spot for sharpness?

The short answer is probably somewhere between f/4 and f/8. The real answer is, once again, it depends. It depends on your camera’s sensor size and the quality of your lens. You have to check for yourself where both diffraction and lens corner problems are minimized.